How The Path Is Changing For Emerging Tecnologies

As emerging technologies drive new business and service models, governments must speedily create, modify, and enforce regulations. The preeminent consequence is how to protect citizens and ensure fair markets while letting innovation and businesses flourish.

Introduction

Sweeping technological advancements are creating a sea modify in today'due south regulatory environment, posing significant challenges for regulators who strive to maintain a balance between fostering innovation, protecting consumers, and addressing the potential unintended consequences of disruption.

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, big data analytics, distributed ledger applied science, and the Net of Things (IoT) are creating new ways for consumers to interact—and disrupting traditional business models. Information technology's an era in which machines teach themselves to acquire; autonomous vehicles communicate with one other and the transportation infrastructure; and smart devices respond to and anticipate consumer needs.

In the wake of these developments, regulatory leaders are faced with a key challenge: how to all-time protect citizens, ensure off-white markets, and enforce regulations, while allowing these new technologies and businesses to flourish?

The supposition that regulations tin can exist crafted slowly and deliberately, then remain in identify, unchanged, for long periods of time, has been upended in today'south environs. Equally new business concern models and services emerge, such equally ridesharing services and initial coin offerings, government agencies are challenged with creating or modifying regulations, enforcing them, and communicating them to the public at a previously undreamed-of step. And they must do this while working within legacy frameworks and attempting to foster innovation.

As seen from the history of early automobile regulation (see "A history lesson" sidebar), tough restrictions on motor vehicles—laws designed to protect pedestrians, horse-fatigued carriages and even cattle—delayed advances in automobile development past decades. Today, regulators face like challenges. They must rest their charge to protect citizens with advancing innovation in new technologies and businesses, resisting the urge to overregulate.

This study is the first in a series of Deloitte papers on the future of regulation. The side by side report will explore how regulators tin utilize technologies and tools like machine learning, text analytics, and blueprint thinking to dramatically alter the way they operate, generate efficiencies, cut costs, and increase compliance and adoption.

This newspaper begins by exploring the unique regulatory challenges posed by digital-age technologies and business models. Section two describes the 4 critical questions policymakers and regulators must accost when information technology comes to regulating the digital economic system. Finally, section three provides a set of five principles to guide the future of regulation:

- Adaptive regulation. Shift from "regulate and forget" to a responsive, iterative approach.

- Regulatory sandboxes. Prototype and exam new approaches past creating sandboxes and accelerators.

- Outcome-based regulation. Focus on results and performance rather than course.

- Risk-weighted regulation. Movement from one-size-fits-all regulation to a data-driven, segmented approach.

- Collaborative regulation. Align regulation nationally and internationally past engaging a broader set of players beyond the ecosystem.

Challenges to traditional regulation

Scholars accept identified a host of challenges emerging technologies present to traditional regulatory models, ranging from coordination problems to regulatory silos to the sheer volume of outdated rules.1 Nosotros accept grouped iv of the near important challenges into two buckets: business and technological (see effigy 1).

Business challenges

The pacing trouble

"Can regulators keep up with fintech?"two "Drone regulators struggle to keep upward with the chop-chop growing technology."3 "Regulatory scramble to stay ahead of self-driving cars."4 "Digital health dilemma: Regulators struggle to keep pace with wellness care engineering science innovation."5 Headlines like these capture a central challenge to today's regulators.

Existing regulatory structures are oft tedious to adapt to changing societal and economic circumstances, and regulatory agencies generally are risk-averse. Rapid adaptation to emerging technology, therefore, poses meaning hurdles—and, in turn, to the technology industries, where change occurs at a rapid rate.

"If the volume and footstep of digital transformation continues to remain the way information technology is, the existing regulatory approach won't piece of work," says Bakul Patel, the US Food and Drug Assistants (FDA)'s acquaintance center managing director for digital health. The gap betwixt technological advancements and the mechanisms intended to regulate them—often called the "pacing problem"—is only growing wider. "There's a disconnect between the speed, iterative development and ubiquitous connected nature of digital health technologies and the existing regulatory structures and processes," says Patel. "The current regulatory approach is not well-suited to back up that fast pace of development."6

The pacing problem has acquired new urgency due to the speed with which mod innovations are scaling.7 Digital products, services, and industries tin can get very large, very fast. The policy cycle frequently takes anything from five to 20 years whereas a unicorn startup can develop into a company with global accomplish in a matter of months. Airbnb, for example, went from 21,000 arrivals in 2009 to 80 million in 2016.8 Meanwhile, cities and states are still trying to figure out how, and if, they can regulate brusk-term rental markets.nine Ride-hailing services take experienced similar hyper-growth equally regulations in the space struggle to adapt.x

Tightening regulation for new, high-visibility industries brings new political and shareholder pressures. It's one thing if regulation slows the launch of new firms or industries—and quite another if it strangles their growth.

Financial organizations—or "fintech"—are expected to concenter more than $46 billion in investment past 2020.11 Merely this will depend, in part, on regulation. According to one survey, 53 pct of Asian fintech investors cite tightening regulations as i of the biggest challenges to fintech, second simply to risk management, and 89 pct believe these regulations volition continue to tighten.12

Manufacture regulatory challenges are compounded by the existing patchwork of regulations. Many national regulatory systems are complex and fragmented, with various responsible agencies exercising overlapping authority. The trade friction resulting from the redundancies and patchworks of regulation lies at the very heart of today's trade agenda.

Coordinating with regulators across borders is another challenge. Since the belatedly 1980s, many organizations and consortia accept cropped up to serve equally independent standards-cosmos bodies that accommodate the unique needs of emerging technology sectors.13

Disruptive concern models

Many information-economy activities have developed in utter disregard of the executive branch organization chart, cascading around and across existing lines of authorization.20—Julie E. Cohen, professor of law and engineering science, Georgetown Law School

Disruptive forms of technological alter often cross traditional industry boundaries. As products and services evolve, they can shift from one regulatory category to some other. For instance, if a ride-hailing company begins delivering food, it tin fall under the jurisdiction of health regulators. If it expands into helicopter service, it volition fall under the purview of aviation regulators. If it uses autonomous vehicles for passengers, information technology may come under the jurisdiction of telecommunications regulators.21

Despite facing often challenging regulatory regimes, ride-hailing companies have grown chop-chop and have put an enormous amount of pressure on traditional regulatory regimes. Maintaining consistency in rules and regulations is specially difficult in the sharing economic system, which oftentimes blurs lines between vendors, facilitators, and customers.

The evolving, interconnected nature of disruptive business models too tin brand information technology hard to assign liability for consumer harm. For case, if a self-driving machine crashes, who is liable—the software programmer, automobile possessor, or the occupant?

Volvo Cars, the Swedish automaker, expects liability to shift from the driver to the manufacturer. "Carmakers should take liability for any system in the car," Anders Karrberg, vice president of government affairs at Volvo Car Corp., told the U.S. Firm Energy and Commerce Committee'due south Digital Commerce and Consumer Protection subcommittee. "So, nosotros have declared that if there is a malfunction to the [driving] organization when operating apart, we would take the product liability."22

Similarly, consider 3D-printed products. How should product liability laws be applied? Who is liable if 3D-printed furniture fails? Is it the store that printed the office, the supplier of the design, or the printer manufacturer?

In the case of virtual currencies, the anonymous, decentralized nature of transactions presents a specially difficult challenge for regulators. In June 2016, the Decentralized Autonomous System—a projection using the Ethereum blockchain-based platform—was tuckered of $55 1000000 when an assaulter exploited a flaw in the code.23 To date, the culprit hasn't been identified and questions of liability remain.24 In this example and others, the properties that make engineering appealing also can allow scam artists and hackers to take advantage of the industry's overall lack of maturity.25

Technological challenges

We have a legal, regulatory framework built on the ground of mail, newspaper, words, versus a new world social club which is digital, continuous, 24/7, and built on bits and bytes. Somehow nosotros need to foursquare these 2 worlds.26—Aaron Klein, policy manager, Heart on Regulation and Markets, Brookings Establishment

Data, digital privacy, and security

The growing utilize of smartphones, continued devices, and sensors has created a vast digital footprint in consumers' lives—a trend that will only accelerate.

From a regulatory perspective, one important question is who owns all this data—the user or the service provider who stores it? If the service provider owns the information, what obligation does it have to store and protect it? And to what extent tin data exist shared with third parties? Can a car manufacturer charge a higher cost to automobile owners who refuse the right to share their private data and less to those willing to share their information?

With no unmarried global agreement on information protection, regulators effectually the globe are taking different positions on these problems. Almost 30 percentage of nations have no data protection laws.27 Those that practice, often have conflicting laws.28 The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for instance, enshrines the principle of privacy, providing strict controls over cantankerous-edge information transmissions and giving citizens the right "to be forgotten."29 In a survey, 82 pct of Europeans say they plan to use their new rights to see, limit, or erase their information.xxx The US approach, by contrast, focuses on sector-specific rules (such equally health care, financial, and retail) and state laws.

One emerging sector impacted by data regulation is digital health. A key development in digital wellness technology is Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), which tin can diagnose medical conditions, suggest treatments, and inform clinical management. SaMD allows patients to play a more than active role in their ain health care.

Regulatory agencies by and large take regulated SaMD in much the same way every bit traditional medical devices such equally eye stents. As the FDA has noted, withal, this approach isn't "well-suited for the faster, iterative design, development, and blazon of validation used for software-based medical technologies."31

A stent remains untouched by the device maker once it's released into the market. Software developers, though, can make continuous changes to their products remotely, afterwards release. These changes may exist related to security, feature updates, or improvements based on the data collected from users. Merely current regulatory practices emphasize vetting before products are released.

Another key regulatory challenge in the digital arena is cybersecurity.32 "Malicious cyberactivity has proliferated," says the EC's Andrus Ansip. "It has become more brazen and sophisticated, more imaginative, and international."33 Cybersecurity is particularly critical in areas such as fintech, digital wellness, digital infrastructure, and intelligent transportation systems. The financial services industry was attacked 130 million times in 2017, while cyberattacks in the payment space alone have risen past 452 percent since 2015.34

In the digital wellness field, SaMDs continually collect and analyze data on medical images, physiological status, lab results, and more, raising potentially serious concerns about the protection of patient data. Autonomous vehicles could be targets of cyberattacks likewise. What precautions should developers of democratic vehicles take to ensure malicious hackers won't force vehicles to crash or manipulate signals to crusade traffic jams?

AI-based challenges

In an April 2017 poll by survey house Morning Consult, 71 per centum of respondents felt there should be national regulations on AI in the Us, and 67 percent chosen for international regulations regulating AI technology.35 Yet AI in its various forms poses some of the nigh difficult challenges to traditional regulation.

The "blackness box" problem. Algorithms today make scores of strategic decisions, from approving loans to determining heart-assault take a chance. Given the importance of algorithms for consumers and businesses, it is important to understand them and make sense of their decisions. Only algorithms frequently are closely held by the organizations that created them, or are so circuitous that fifty-fifty their creators can't explain how they work. This is AI's "black box"—the inability to run into what's inside an algorithm.

In response, some experts in the field have suggested making algorithms open up to public scrutiny. Many aren't fabricated public considering of nondisclosure agreements with the companies that developed them. That'southward likely to change, however, at least in the European Matrimony. In May 2018, the GDPR went into consequence requiring companies to be able to explain how algorithms using the personal data of customers piece of work and make decisions.36

Algorithmic bias. Algorithms are routinely used to make vital financial, credit, hiring, and legal decisions. In theory, this should lead to unbiased and fair decisions. Simply some algorithms have been found to have inherent biases. And while in some countries regulations explicitly prohibit bigotry in these and other areas, gray areas exist and oft the underlying algorithms are opaque.

"People are basically getting or not getting those things that they need based on scores that they don't understand and sometimes don't even know exist," says Cathy O'Neil, author of Weapons of Math Destruction. "Right at that place y'all already have something very dangerous."37

A widely cited example of algorithmic bias was found in a written report conducted by Harvard faculty member Latanya Sweeny. Her written report concluded that searches for stereotypical African-American names are upward to 25 percent more than likely to exist displayed alongside an abort-related ad. Sweeney gathered this evidence past collecting more than 2,000 names suggestive of race. For example, offset names such as Terrell, Tyrone, and Ebony advise the person is blackness, while Amy, Jake, and Emma suggest the person is white.38

The critical questions

Equally government policymakers and regulators grapple with the regulatory challenges posed by digital technologies, four foundational questions are critical to address (see figure 2):

- What's the current state of regulation in the area?

- What'due south the right time to regulate?

- What'southward the right arroyo to regulation?

- What has changed since regulations were first enacted?

one. What'south the electric current state of regulation?

The kickoff footstep in the preregulatory phase should involve a thorough review and agreement of pertinent existing regulations, looking for those that might exist blocking innovation, are outdated, or are duplicative. By electric current state, nosotros refer to the whole ecosystem of regulation that could apply: from vertical service or sector regulation, for example, for motor vehicles; to convergent regulation where multiple sectors are involved; to lateral regulation such as employment or business concern licensing.

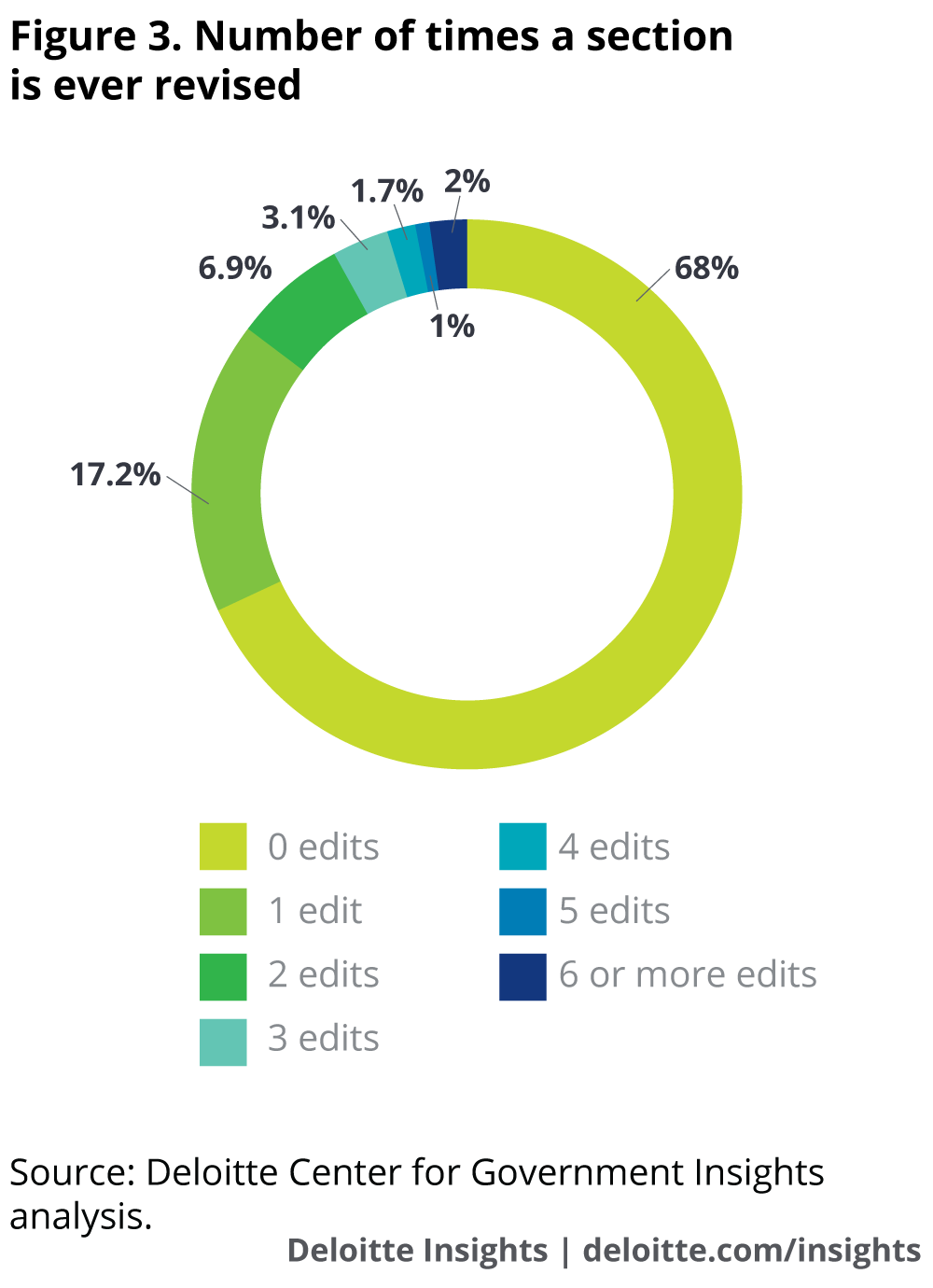

Often such a review hasn't been washed in many years. A Deloitte analysis of the 2017 US Lawmaking of Federal Regulations found that 68 pct of federal regulations take never been updated (come across effigy iii).39

A retrospective review forces regulators to evaluate whether alternatives to regulation or adjustments to current rules could adequately accost the perceived problem.xl Kingdom of denmark, for example, has created a chore force to claiming outdated legislation and regulations in the wake of disruptive business concern models.41 The Danish Ministry of Surroundings and Food is dwelling to one of the more aggressive regulatory modernization efforts. This includes cutting the number of regulations in its portfolio by one-third, plans to slash the number of laws it administers from 90 to 43, and an update of all existing laws to adjust to the digital age.42

2. What's the correct fourth dimension to regulate?

How can regulators avoid the besides fast or besides slow problem? A number of the principles outlined in the next section of the paper (peculiarly principles one and 2, adaptive regulation, and regulatory sandboxes) are designed to assistance answer the when question by both bringing regulators closer to the technological innovations while also shifting to a more agile regulatory model.

iii. What'due south the right regulatory approach?

Policymakers have a host of reasons for regulating, but generally, they are trying to protect citizens, promote contest, and/or internalize externalities. Which of these reasons is well-nigh important in a given situation volition impact how to respond the next critical question: What'south the best regulatory model to use? A wide variety of potential approaches exist between heavy, precautionary regulation on ane stop of the spectrum and footling to no regulation on the other end (see effigy ii).

And indeed, in areas ranging from cryptocurrencies to autonomous vehicles, we're seeing regulatory models across the spectrum. Consider regulations pertaining to unmanned aerial systems (UAS), or drones. Governments have increasingly opted for ane of two paradigms in edifice regulatory systems: UAS Allowance (broader permissiveness of UAS usage) or UAS restriction (usage permitted but within specific limits).

When answering the "what is the right approach?" question, an important consideration is what regulation scholar Adam Thierer calls "global innovation arbitrage." As he explains: "Capital moves like quicksilver around the world today as investors and entrepreneurs look for more hospitable tax and regulatory environments. The same is increasingly true for innovation. Innovators can, and increasingly volition, move to those countries and continents that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity."43

We have already seen this scenario play out with genetic testing, unmanned aerial systems, autonomous vehicles, and the sharing economy.

4. What has changed since regulations were first enacted?

Considering the rapid rate at which emerging technologies are progressing and business models evolving, it is a good bet that in society to stay relevant, regulations applied today volition need to be revisited within the next decade or so. There are a variety of ways to institutionalize such automatic reviews; these range from regulatory sunsetting with periodic review44 to processes like the European Union's Regulatory Fitness and Performance (REFIT) plan, which conducts retrospective evaluations to look for laws that are obsolete or in need of revision.

Principles for regulating emerging technologies

The following five principles tin can both help to answer the "when to regulate" and "how to regulate" questions likewise as set a foundation for rethinking regulation in an era of rapid technological change (see effigy iv).

1. Adaptive regulation

Shift from "regulate and forget" to a responsive, iterative arroyo.

Rapid alter, pivoting business models, and experimentation are hallmarks of technology-driven businesses—but are rarely the norm in regulation.

Traditionally, regulators conceptualize new rules and regulations in response to market developments or new legislation. Next, they spend months or years drafting rules and presenting a start draft for public comment. Finally, they examine these comments—and there can be tens of thousands or even millions of them—and change the proposed draft accordingly.

The problem with this process is twofold: Commencement, regulators often don't really know how businesses and consumers will react to new regulations; and second, the rules are rarely reconsidered once in effect.45

Adaptive approaches to regulation, on the other mitt, rely more than on trial and error and co-design of regulation and standards; they also have faster feedback loops. More rapid feedback loops allow regulators to evaluate policies confronting set up standards, feeding inputs into revising regulations. Regulatory agencies have a number of tools to seek such feedback: setting upwards policy labs, creating regulatory sandboxes (detailed in the next department), crowdsourcing policymaking, and providing representation to industry in the governance process via self-regulatory and private standard-setting bodies.46

The National Highway Traffic Prophylactic Assistants (NHTSA)'due south 2016 Federal Automatic Vehicles Policy offers an case.47 Past taking an iterative arroyo in designing policy for autonomous vehicles, the NHTSA responded to new information and technologies to make meaning revisions to its initial policy of 2017.48

Soft law mechanisms—instruments or arrangements that create substantive expectations that are not directly enforceable—offering another tool for shifting to more than adaptive regulation.49 Unlike difficult police force requirements such equally treaties and statutes, soft police force tin can include informal guidance, a button for industry self-regulation, best-practice guidance, codes of bear, and third-party certification and accreditation.

While non legally binding, soft police instruments take several advantages over formal regulation in the loonshit of emerging technologies. They allow regulators to adjust quickly to changes in applied science and business models, and to address issues as they arise without stifling innovation.l Moreover, through deep appointment with afflicted stakeholders, they help regulators understand the nuances of the engineering science and its potential impacts.

One way regulators can apply soft police force is to define the scope of issues to be addressed and enquire manufacture to develop its ain standards and codes of deport in response. Elizabeth Denham, the U.k.'s information commissioner, has said that regulators should develop broad principles so that industry leaders can develop standards to marshal with them.51 Regulators so can certify the standards adult past private industry.

Concept in practice: Finland reforms its transportation regulation

Finnish officials recognized the demand to reform their transport regulations to support their vision of mobility-as-a-service (MaaS), which considers transportation as an integrated system of dissimilar services. "We have to look at the transport organization every bit one entity, with no borders and the ability to share data on payments, tickets, and location," says Anne Berner, Finland'due south minister of transport and advice.

Hence, the country decided not to reform or revise dissever laws on taxis, public transport, roads, or the transport of goods but instead to create a new integrated transportation code. "We decided to remove those onetime laws and create a new transport code that incorporates all transport modes into one piece of legislation, to be technology-neutral, and to create the aforementioned level playing field for different ship modes," Berner says. The aim is to deregulate existing transport while building the foundations for MaaS.52

two. Regulatory sandboxes

Prototype and test new approaches past creating sandboxes and accelerators

An accelerating trend for regulatory agencies is the creation of accelerators and "sandboxes," in which they partner with private companies and entrepreneurs to experiment with new technologies in environments that foster innovation. "The role of a regulator is no longer just a regulator; information technology's more of a partner in bringing safe and effective technologies to the tabular array for people to have that loftier conviction in those technologies," says the FDA's Patel.53

Accelerators are designed to speed up innovation. They oft involve partnerships with private companies, bookish institutions, and other organizations that can provide expertise in certain areas. Sandboxes are controlled environments allowing innovators to examination products, services, or new business organisation models without having to follow all the standard regulations (encounter figure five).

The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), for example, launched a regulatory sandbox that provides time-limited relaxation from sure regulatory requirements placed on startups.54 "The objective of this initiative is to facilitate the ability of those businesses to apply innovative products, services, and applications all across Canada, while ensuring appropriate investor protection," says Louis Morisset, CSA chair and president and CEO of the Autorité des Marchés Financiers.55

Impak Finance, for case, became the starting time company ever to legally enhance $1 million via a cryptocurrency crowdsale in the Americas.56 Every bit office of the CSA sandbox, it was exempted from registering as a security dealer and providing a prospectus. Impak will be immune to remain in the sandbox for two years.57

Meanwhile, the United states is piloting a sandbox approach for unmanned aeriform systems (UAS). The Department of Transportation's Federal Aviation Assistants has chosen 10 public-private partnerships to test UAS. "The airplane pilot programs will test the safe performance of drones in a diversity of conditions currently forbidden," says Transportation Secretarial assistant Elaine Chao. These include operations over the heads of people, beyond the line of sight, and at night. "Instead of a dictate from Washington, this program takes another approach," Chao says. "It allows interested communities to test drones in means that they're comfortable with."58

Sandbox approaches are intended to assistance regulators better understand new technologies and work collaboratively with manufacture players to develop appropriate rules and regulations for emerging products, services, and business concern models.59

Sandboxes are not without their detractors who worry regulators might get too shut to the startups and endeavour to prop them up if they stumble in the market.60 With this in listen, the Brookings Institution's Aaron Klein suggests a improve metaphor might be that of a greenhouse: "A greenhouse is a thing in which small plants are put into full sunshine and transparency and allowed a unique environment that's different from the outdoor surroundings. By definition, it's more protected and hospitable, and in time, it allows the plants to abound and flourish. Some of the companies in your greenhouse might fail, merely like some plants in your garden die; others will grow and flourish, just there's full transparency, with some protection."61

Concept in practice: The United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland Financial Conduct Authorization's regulatory sandbox

The United kingdom has been a pioneer in the use of accelerators and sandboxes as part of the regulatory process. Its Fiscal Conduct Authority (FCA), equally office of its broader Projection Innovate, launched the first fintech regulatory sandbox in June 2016. This sandbox allows businesses to test innovative products and services in a safe, alive surroundings, with the appropriate consumer safeguards, and, when appropriate, is exempt from some regulatory environments.62 After its first year of operation, xc percent of firms that completed testing in its get-go cohort were continuing toward a wider marketplace launch, and more than 40 per centum received investment during or following their sandbox tests.

The FCA released a report on what it learned from its commencement year. Some central lessons include:

- Reduced time to market. Access to the regulatory expertise the sandbox offers reduced the time and toll of getting innovative ideas to market.

- Facilitated investor funding. The feedback received from participating firms indicated that investors tin exist reluctant to piece of work with companies not yet authorized past the FCA due to regulatory incertitude.

- Product and market testing. Many firms in the sandbox used the platform to assess the consumer traction and viability of their business models. Testing in the live environment helped businesses understand consumers' reception to new pricing strategies or new technologies. This enabled them to constantly iterate on the business model.63

- Testing viability of the underlying technology. The FCA conducted technology and cybersecurity reviews of the firms when setting upwards the sandboxes. This allowed the firms to test the viability of their underlying technology and build in appropriate measures to minimize cyber risk.64

- Better consumer safeguards. Working closely with the FCA encouraged fintech startups to develop business organization models that mitigated risks for consumers. For example, all firms testing the apply of digital currency for payment transfers were required to guarantee the funds beingness transferred and pay total refunds if they were lost in transfer.65

- Reduced challenges in data sharing. For a few firms, their business concern model relied on obtaining users' transactional data on loans, credit cards, current accounts, and pension balances from other financial institutions. Without a formal machinery for data sharing in place, it was hard for such firms to directly approach institutions.

3. Outcome-based regulation

Focus on results and performance rather than form

Traditionally, regulations take tended to be prescriptive and focused on inputs. When the focus of regulation shifts from inputs to outcomes, the way regime intervenes in markets changes. This shift can create operational efficiencies for regulators and greater freedom for innovators.

Outcome-based regulation specifies required outcomes or objectives rather than defining the way in which they must exist achieved. This model of regulation offers businesses and individuals more freedom to choose their manner of complying with the constabulary.

Prioritizing functioning and outcomes enables governments to develop regulations (or other, softer mechanisms such every bit guidelines) that focus on the positive effects regulators are looking to encourage (or the negative effects they're looking to prevent). Consider three different ways of structuring UAS regulations:

- You lot must have a license to fly a drone with more than than xx kilowatts of power (input—not very helpful).

- Y'all cannot wing a drone higher than 400 feet, or anywhere in a controlled airspace (output—better).

- You cannot fly a vehicle in a way that endangers human life (outcome—best; addresses the touch or consequence information technology has).

Ofttimes, emerging technologies' real potential tin can exist harnessed merely when they are meshed together, such as using blockchain to secure data generated by autonomous vehicles, or using a combination of auto learning and natural language processing to prescribe medication via a chatbot. For such connections to happen, innovators need room to introduce. Consequence-based regulation can provide the leeway needed to experiment.

Concept in practice: Australia's guidelines for democratic vehicles

Commonwealth of australia has developed performance-based guidelines for autonomous vehicles. "Guidelines are preferable to legislation as they let the flexibility to be speedily amended and updated, if required," states a policy paper by Australia's National Transport Commission (NTC). The newspaper goes on to say that regulations for automated vehicles should be "proportionate, operation-based, and regularly reviewed."66

Paul Retter, NTC chief executive, believes multiple issues should be addressed before making autonomous vehicle a reality on the road. "Our focus is on ensuring the regulatory system remains flexible plenty to accommodate evolving technologies as they come up to market while e'er prioritizing public safe," says Retter.

Industry stakeholders also are evaluating performance-based standards. The Australian Automobile Clan suggests that standards for automated vehicles should be operation-based and engineering-agnostic, and that the responsible parties and processes for certifying vehicle modifications should be clearly identified and unambiguous.67

iv. Adventure-weighted regulation

Shift from ane-size-fits-all regulation to a data-driven, segmented approach

Speed to market place is imperative for businesses, especially startups with business concern models predicated on emerging technologies. Speed to market as well can make digital services and products more effective. As they are used, they unremarkably collect data on their users. With the help of advanced analytics and, in many cases, AI, the data can then be analyzed to discover new patterns and trends, information that tin can make the product more than accurate, safe, effective, and personalized. Because of this iterative cistron, the sooner safe and effective products become to the market place, the better.

One way to accelerate the approval of business models based on emerging technologies would be to describe inspiration from the precheck systems for airline travel used in many countries. These work by using data to certify low-risk flyers, who then receive a lower level of scrutiny and inspection.

A similar approach could be used to aid expedite approvals of new business organization models. It would let certain companies to become through a streamlined and anticipated approving process, contingent on their providing admission to key data.

The Land of New Jersey allows commercial trucks enrolled in NJPass to featherbed counterbalance stations. Qualification is based on their Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration rating and data on history of roadside inspections.68 "This system [focuses] on college-run a risk carriers and provide[s] more efficient utilize of our limited New Jersey Land Police resources," explains Paul Truban, NJDOT's manager of the Agency of Freight Planning and Services.69

A data-driven, take a chance-based arroyo shouldn't be merely limited to preapprovals, however. It tin be extended to a dynamic, regulatory approach, based on existent-time data flows between companies and their regulators. Already, many regulatory bodies, from the U.s.a. Securities and Exchange Commission to the European Commission, have established such data flows with manufacture.lxx

The resulting data could and so be analyzed and compared with regulations or expected outcomes to decide whether a firm is in compliance. Firms in compliance would be listed equally safe, and if not, the data systems could produce a set of activity items to meet the standard, or, in the example of a more serious violation, issue reprimands or penalties such as removal from the safe listing.

Regulators also tin can use open information to complement their own information or for independent inspection. In the example of digital wellness software, a regulator could monitor products through publicly available information on software bugs and error reports, customer feedback, software updates, app store information, social media, and GitHub.71 Once the data flows are integrated, this part of the regulatory process tin be automated. Enforcement can become dynamic and reviewing and monitoring can be built into the system.

Consider an experiment in the city of Boston. The city's usual food safety process, which relied on random selections of restaurants for further scrutiny, needed comeback. The city'southward data portal72 hosts public data on restaurant nutrient safe inspections also as many other aspects of metropolis life. To more effectively place restaurants in need of regulatory attention, the city collaborated with Yelp and Harvard Business Schoolhouse to sponsor an open competition to develop an algorithm that could predict health code violations. More than 700 contestants participated, using eatery inspection information and years of Yelp reviews.73

While participants analyzed the reviews, looking for mutual words and phrases,74 Harvard economists evaluated the submissions confronting the city'due south actual inspection reports. The verdict: The winning algorithm could improve inspectors' power to notice violations by 30 percent to 50 per centum.75

Yet another form of risk-based regulation could lower the high entry toll of regulatory certification. Daniel Castro of the Center for Data Innovation suggests moving to a "cloud computing model of regulation," in which scalability is built into the regulatory model. For case, if a visitor's production or service were targeted toward just a few users, it might receive fewer checks since its potential adverse impact would exist limited. Only later that company grew and began selling its products more widely would it meet a more thorough investigation.76

Concept in practice: The FDA's Pre-Cert process

For certain digital wellness products, the FDA already uses hazard-based approaches that balance potential risks with patient benefits.

Every bit function of its Digital Health Innovation Action Plan, the FDA created a Pre-Cert pilot program for eligible digital health developers that demonstrate a culture of quality and organizational excellence based on objective criteria—for example, excelling in software design, development, and testing. The airplane pilot intends to await "starting time at the software developer or digital health technology developer, non the production."77

The idea behind this is to allow the FDA to accelerate time to market for lower-adventure health products and focus its resources on those posing greater potential risks to patients. Precertified developers could market place lower-risk devices without additional FDA review, or with a simpler premarket review.

But precertification is just one function of the model; the FDA intends to monitor the performance of these companies continuously, with existent-world data. Scorecards and corresponding Pre-Cert levels could go up or downward based on performance and effectiveness data. If scores fall below a divers threshold, the system might lose certain benefits, such as expedited reviews for less-risky products or eligibility for Pre-Cert status until it can resolve whatever product issues through a new cess.78

v. Collaborative regulation

Marshal regulation nationally and internationally by engaging a broader set of players across the ecosystem

A recent global survey of more than 250 experts and leaders of financial institutions indicated that regulatory divergence—inconsistent regulations across different nations—costs financial institutions from 5 percent to 10 percent of their annual revenue. The patchwork of international financial regulations costs the global economy $780 billion annually.79

As the digital economic system expands, with new business models, technologies, products, and services, regulators around the earth tin benefit from collaborative approaches such as co-regulation, self-regulation, and international coordination. Through multi-stakeholder meetings that produce concrete policy guidance and voluntary standards, regulators and firms besides as other interested parties can be engaged in the process.

This ecosystem approach—when multiple regulators from different nations interact with one other and with those beingness regulated—can encourage innovation while protecting consumers from potential fraud or safety concerns. In this approach, private, standard-setting bodies and cocky-regulatory organizations as well have cardinal roles to play in facilitating collaboration between innovators and regulators.

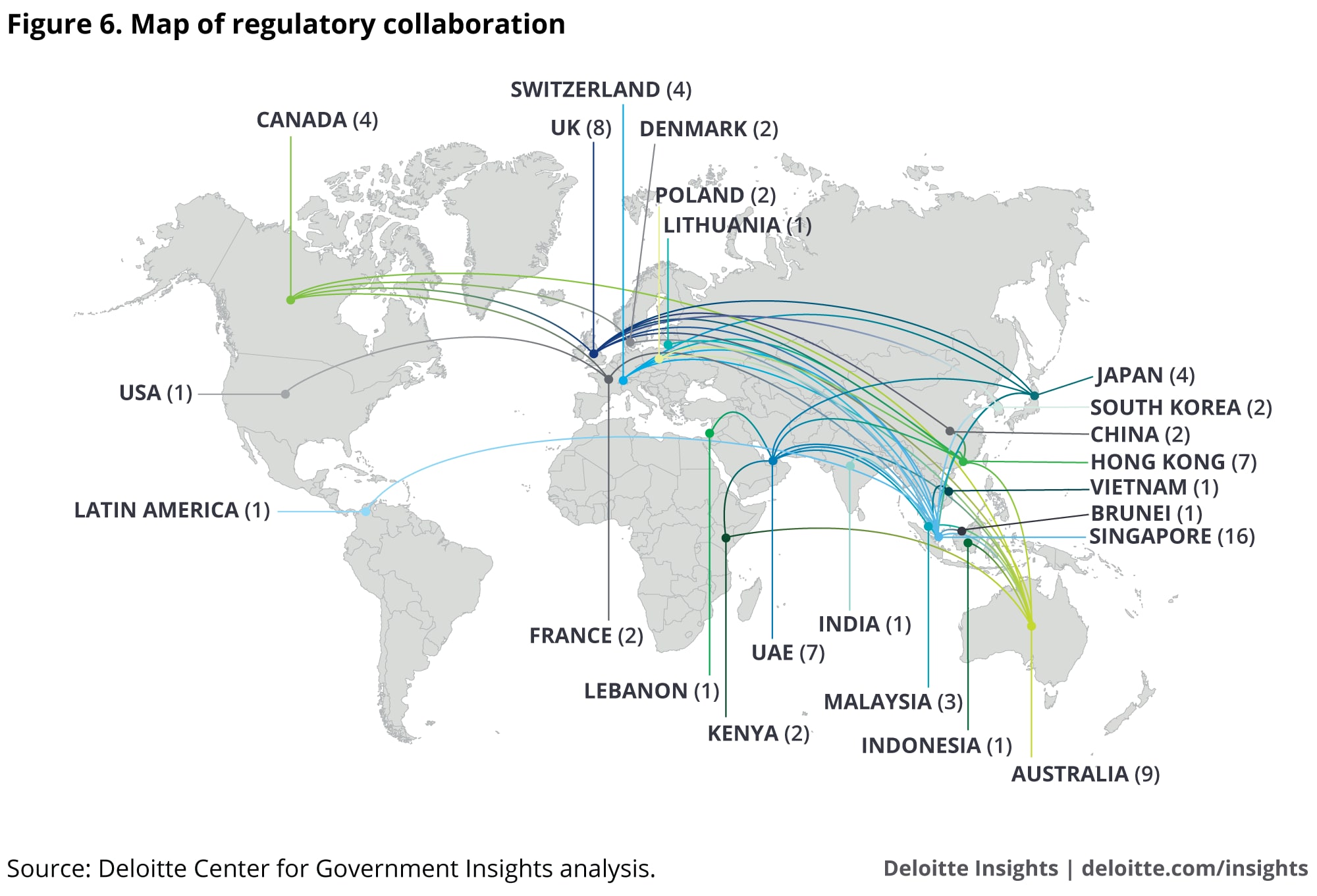

The fintech space has shown glimpses of regulatory convergence (run into figure vi). For instance, Singapore has signed 16 agreements with entities in xv different countries. These agreements include information exchanges with other nations' regulators and regulated businesses, referrals of firms attempting to enter a regulatory partner's nation, and guidance for companies on the regulations of nations they wish to enter.lxxx Such agreements could lead to standard frameworks and guidelines across nations.

Global and regional institutions can play a key role in facilitating these cantankerous-border agreements. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, for example, enables cross-border data flow amid its members through a gear up of principles and guidelines designed to found cross-edge privacy protections while fugitive barriers to information flows. Businesses agree to follow the privacy rules; independent entities monitor and concord the companies accountable for privacy breaches.81

Concept in do: Internet governance and multi-stakeholder engagement

In certain instances, regulators tin can do good from working directly with businesses, innovators, and other players to define rules for emerging technologies. For example, the internet's decentralized, global structure defied regulatory logic and demanded a new framework to address its revolutionary nature.

In 1997, afterwards because various regulatory approaches to internet governance, the Clinton Administration released a gear up of principles called The framework for global electronic commerce to guide the development of digital communications technologies. The framework outlined a number of general principles to guide the government'south treatment of net and forbid ambitious regulatory activity. Amongst these:

- The private sector should pb.

- Governments should avoid undue restrictions on electronic commerce.

- Where governmental involvement is needed, its aim should be to back up and enforce a predictable, consistent, and simple legal surroundings for commerce.

- Governments should recognize the internet's unique qualities.

- Electronic commerce through the cyberspace should exist facilitated globally.82

Taken together, these principles establish a de facto regulatory construction that sidesteps the traditional process for promulgating new rules in favor of a arrangement of co-regulation and multi-stakeholder engagements. Such systems can aid induce constructive dialogue among various stakeholders who might otherwise exist less amenable to compromise.

Conclusion

For technological innovation, regulation can be catalytic—or a hindrance. Equally emerging technologies evolve, regulators from around the earth are rethinking their approaches, adopting models that are agile, iterative, and collaborative to face the challenges posed past emerging technologies and the quaternary Industrial Revolution. To promote innovation, regulators are also moving toward creating outcome-based regulations and testing new models in sandboxes. The principles outlined in this paper tin can help regulators residuum consumer protection and innovation effectively. This is the start study in our series on the future of regulation. Look for our additional papers in the months and years ahead.

Source: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/future-of-regulation/regulating-emerging-technology.html

Posted by: barbourwhered.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How The Path Is Changing For Emerging Tecnologies"

Post a Comment